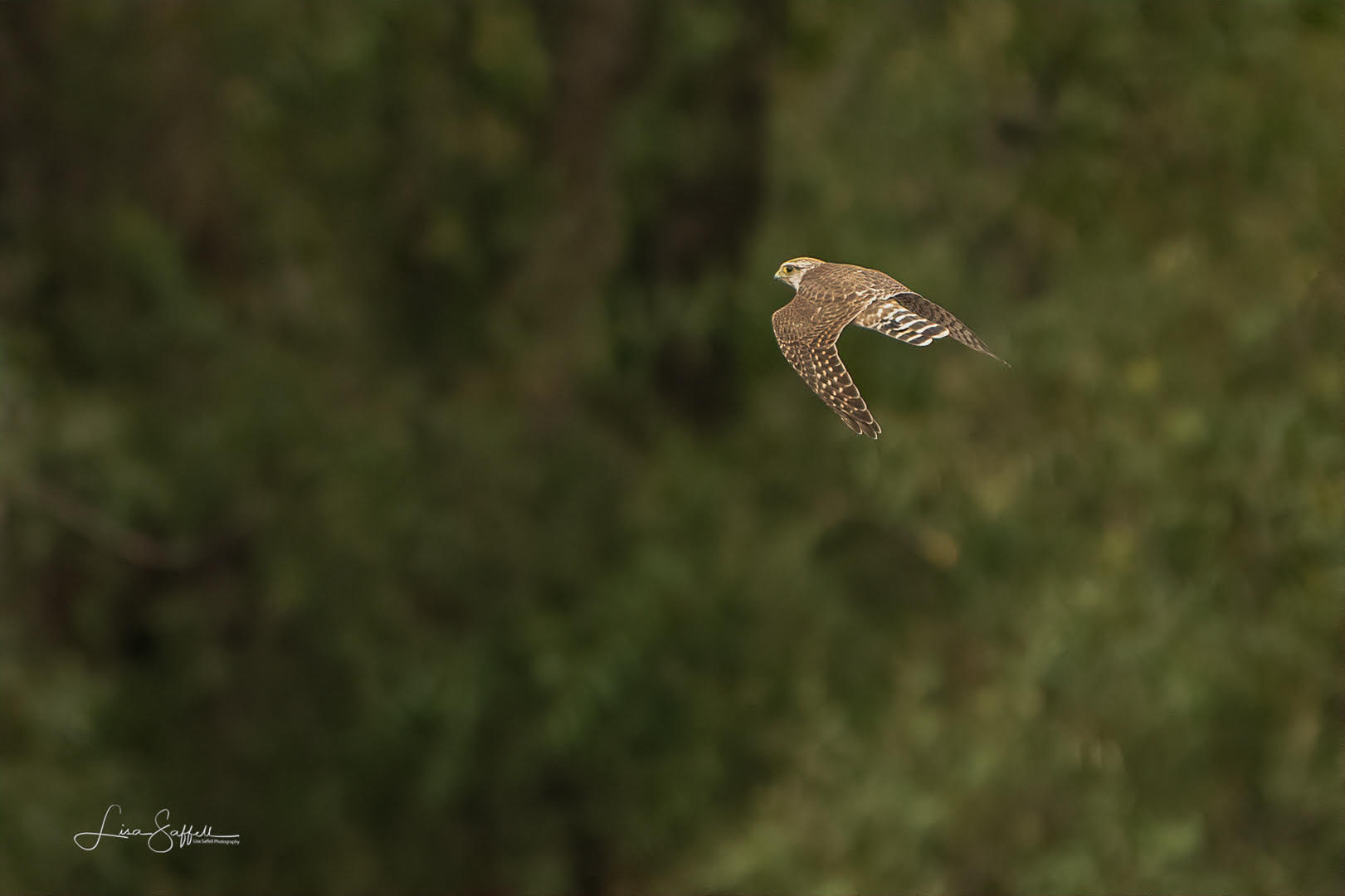

Merlin, Falco columbarius

Bill Rowe

Worldwide, falcons are recognizable by their long, pointed wings, their dashing flight, and their laser focus on pursuing their prey. These qualities have inspired the sport of falconry for millennia, and now they elicit the same fascination among people of all backgrounds who simply enjoy observing birds. North America is home to six true falcons (genus Falco), of which three are commonly seen here in the Midwest: the little American Kestrel and the large Peregrine Falcon (both treated earlier in this series), and this week the Merlin, which is almost as small as a kestrel but more like a peregrine in behavior. A Merlin will appear out of nowhere, bearing down on a flock of birds and causing them either to dive for cover or to bunch up into a tight “flying ball.” Successful or not, with or without its lunch, the Merlin will pull up onto a tree branch or a cornstalk and, with luck, will allow you a few minutes to view it before it takes off again, powering away over the fields and out of sight. Kestrels, by comparison, seem tame as they hover over the grass or scan from power lines for mice and insects—but they are also common and familiar, whereas Merlins preserve more of a mystique by remaining scarce, just the occasional one or two birds in a day (or a month). In Missouri, they are seen fall, winter, and spring, but never as a summer breeding bird. That may change, however: the Merlin’s breeding range has been slowly expanding south from Canada as they adapt to life in towns and cities. They now nest across much of Minnesota and Wisconsin and, within just the past few years, have nested in two Iowa cities not that far to our north. The bigger picture is that Merlins occur worldwide around the Northern Hemisphere, with several subspecies in Europe and Asia. In fact, the name Merlin, originally from French, is one that we adopted from the British when we dropped our former American name for this bird (look under Pigeon Hawk in books before the 1960’s, and while you’re at it, check what we used to call a kestrel, a peregrine, and a harrier).

IDENTIFICATION: All Merlins are heavily streaked below and are uniformly colored on the head, back, and wings, either blue-gray (adult males; see banner photo) or brown (females and juveniles; see below); they lack the rufous color shown by all kestrels. Their tails are dark with pale bands, again unlike the rufous tails of all kestrels. Moreover, their faces have a single rather ill-defined mustache or sideburn mark, unlike the double sideburn of a kestrel or the bold contrasty one of the larger peregrine. One additional thing to watch for: If a Merlin is dark above (like the banner and lower left photos), it belongs to the taiga subspecies, and if it is paler (like the lower right photo) it belongs to the prairie subspecies. We see both around St. Louis.

ST. LOUIS STATUS: An uncommon migrant, mostly March-April and September-November; scarcer in winter.

Learn more and listen to the calls of Merlins here.

Female/juvenile: note dark brown, indicating taiga race

Female/juvenile: note paler brown, indicating prairie race

Photo Credit: Lisa Saffell